November 14, 2016 Profiles in Innovation

Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research 18

GS Research Internet analyst Heath Terry sat

down with Chief Economist Jan Hatzius to

discuss the role AI & machine learning could

play in boosting lagging labor productivity.

Heath Terry: W

hat has led to the lack of

measurable productivity growth over the

last decade?

Jan Hatzius:

A good starting point is the

1990s, where we did have a sizeable

measured productivity acceleration which

was mainly technology driven. The

technology sector had gotten bigger and

measured output growth in the technology

sector was very rapid, and that was enough to produce an overall

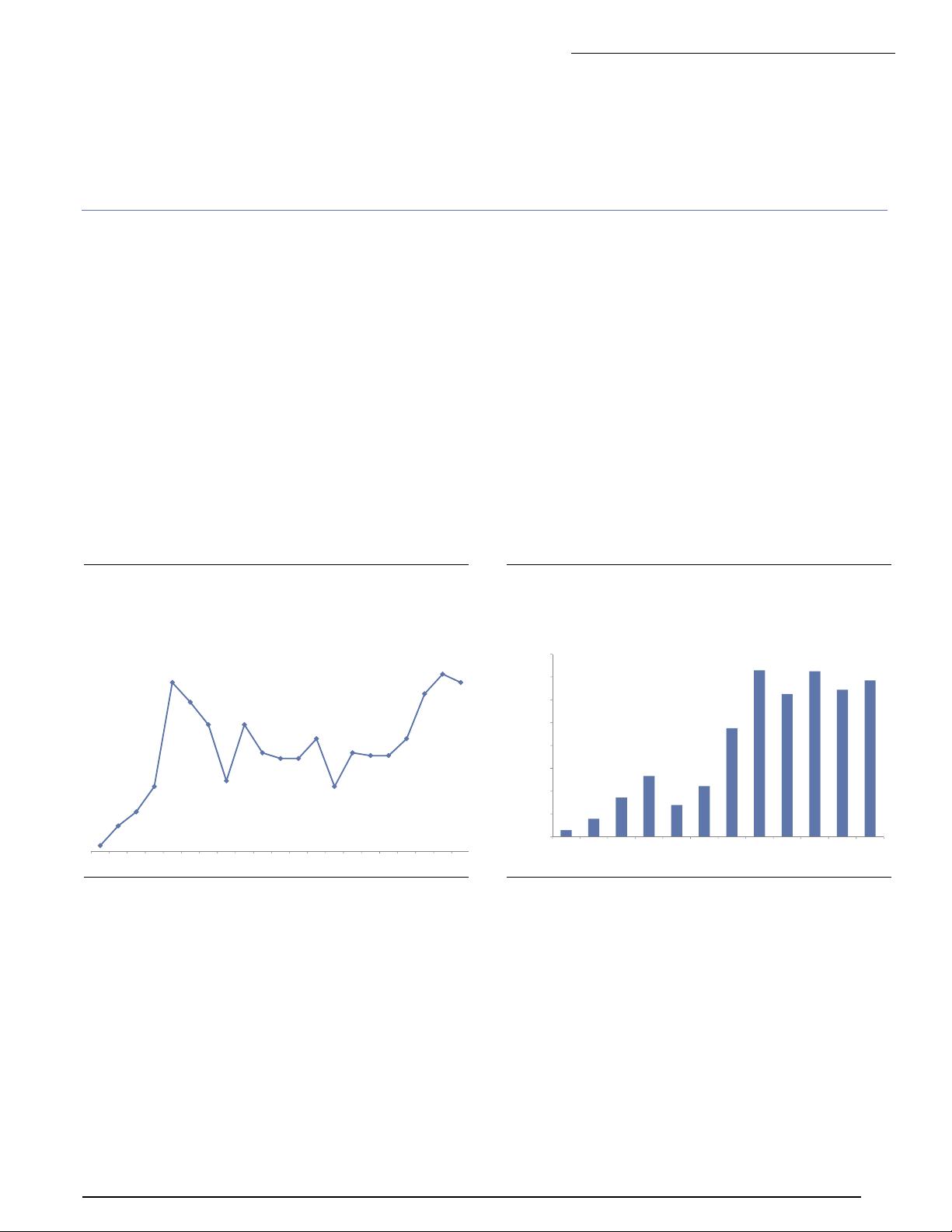

acceleration in the economy. Recently, over the last 10 years or so,

we’ve seen a renewed deceleration to productivity growth rates

that are as low as the 1970s and 1980s, and potentially even lower.

I think there is more than one driver, but I would say there are three

things that have lowered productivity growth in my view. One is a

bit of a cyclical effect. We still have some hangover from the great

recession with a relatively slow pace of capital accumulation,

relatively low levels of investment, and relatively rapid employment

growth. Since productivity is measured as output per hour worked,

that somewhat perversely means that you can have lower

productivity numbers when the labor market is improving rapidly.

Another factor may be some slowdown in the overall pace of

technological progress. It’s reasonable to believe that perhaps the

1990s, with the introduction of the internet, was a relatively rapid

period for technological progress, and I would say there is some

support for the idea that it is a little slower now.

The third point is that technological progress that has occurred

over the last decade, like mobile and consumer focused

technology, is something that statisticians are not very well set up

to capture in the numbers. The reason is that quality improvement

in a lot of the new technologies that have dominated in the last

decade or so is very difficult to capture in a quantitative sense.

Statisticians are not building in significant quality improvement

into a lot of the areas that have been at the cutting edge.

So I would point to three things. There are cyclical effects,

probably some slowdown in technological progress, and very

likely an increase in the measurement error in the productivity

statistics.

Terry: Back to the productivity boom in the 1990s, what role did

technology play?

Hatzius:

What drove it was mainly general purpose technologies

like semiconductors and computers, which had become much

larger as a share of the economy than they were in the 1970s or

1980s and where technological progress was very rapid, in ways

that statisticians were well set up to measure. The statisticians in

the 1990s had made a lot of effort to capture quality improvement

faster; processer speeds, more memory, better attributes in

computer hardware, which led to large increases in the measured

contribution of the technology sector. The technology sector was

very central to pick up in the productivity numbers from the 1990s

lasting to the early and mid-2000s.

Terry:

We’ve seen a lot of technology development over the last

10-15 years. Why hasn’t there been a similar impact to

productivity from technologies such as the iPhone, Facebook, and

the development of cloud computing?

Hatzius:

We don’t have a full answer to it, but I do think an

important part of the answer is the statistical ability to measure

improvement in quality, and the impact of new products in the

economic statistics is limited. It’s relatively easy to measure

nominal GDP, that’s basically a matter of adding up receipts. There

is room for measurement error as there is in almost everything,

but I don’t have real first order concern that measurement is

getting worse in terms of measuring nominal GDP. Converting

nominal GDP numbers into real GDP numbers by deflating it with a

quality adjusted overall price index is where I think things get very

difficult. If you look, for example, at the way software sectors enter

the official numbers, if you believe the official numbers, $1000 of

outlay on software now buys you just as much real software as

$1000 of outlay bought you in the 1990s. There has been no

improvement in what you get for your money in the software

sector. That’s just very difficult to believe. That just does not pass

the smell test. Because of the difficulty of capturing these quality

improvements, the fact that the technology sector has increasingly

moved from general purpose hardware to specialized hardware,

software and digital products has led to increased understatement

and mismeasurement.

Terry:

What kind of impact could the development of technologies

like artificial intelligence and machine learning have on

productivity?

Hatzius: In principle, it does seem like something that could be

potentially captured better in the statistics than the last wave of

innovation to the extent that artificial intelligence reduces costs

and reduces the need for labor input into high value added types of

production. Those cost saving innovations in the business sector

are things statisticians are probably better set up to capture than

increases in variety and availability of apps for the iPhone, for

example. To the extent Artificial Intelligence has a broad based

impact on cost structures in the business sector, I’m reasonably

confident that it would be picked up by statisticians and would

show up in the overall productivity numbers.

I would just add one general caveat, which is that the U.S.

economy is very large. Even things that are important in one sector

of the economy and seem like an overwhelming force often look

less important when you divide by $18tn, which is the level of U.S.

nominal GDP, so the contribution in percentage terms may not

look as large as one might think from a bottom up perspective. But

in principle, this is something that could have a measurable

impact.

Terry: You touched on the impact to cost, how do you see

something like that impacting pricing? Does that become a

contributor to the broader deflationary force that we’ve seen in

certain parts of the economy?

Hatzius: I certainly think that in terms of productivity gains, the first

order impact is often to lower costs and lower prices. Keeping

everything else constant would mean lower overall inflation in the

economy. It’s often not the right assumption that you want to keep

AI & The Productivity Paradox: An interview with Jan Hatzius

起点学院www.qidianla.com,互联网黄埔军校,打造最专业最系统的产品、运营、交互课程。