Connected Fermat Spirals for Layered Fabrication

Haisen Zhao

1

Fanglin Gu

1

Qi-Xing Huang

2

Jorge Garcia

3

Yong Chen

4

Changhe Tu

1

Bedrich Benes

3

Hao Zhang

5

Daniel Cohen-Or

6

Baoquan Chen

1

1

Shandong University

2

TTI Chicago

3

Purdue University

4

USC

5

Simon Fraser University

6

Tel-Aviv University

Abstract

We develop a new kind of “space-filling” curves, connected Fer-

mat spirals, and show their compelling properties as a tool path fill

pattern for layered fabrication. Unlike classical space-filling curves

such as the Peano or Hilbert curves, which constantly wind and bind

to preserve locality, connected Fermat spirals are formed mostly

by long, low-curvature paths. This geometric property, along with

continuity, influences the quality and efficiency of layered fabrica-

tion. Given a connected 2D region, we first decompose it into a set

of sub-regions, each of which can be filled with a single continuous

Fermat spiral. We show that it is always possible to start and end

a Fermat spiral fill at approximately the same location on the outer

boundary of the filled region. This special property allows the Fer-

mat spiral fills to be joined systematically along a graph traversal

of the decomposed sub-regions. The result is a globally continuous

curve. We demonstrate that printing 2D layers following tool paths

as connected Fermat spirals leads to efficient and quality fabrica-

tion, compared to conventional fill patterns.

Keywords: connected Fermat spirals, space-filling curve, layered

fabrication, tool path, continuous fill pattern

Concepts: •Computing methodologies → Parametric curve

and surface models; Shape analysis;

1 Introduction

The emergence of additive manufacturing technologies [Gibson

et al. 2015] has led to growing interests from the computer graphics

community in geometric optimization for 3D fabrication. The fo-

cus of many recent attempts has been on shape optimization: how

to best configure a 3D shape, e.g., via hollowing or strengthening,

to achieve quality and cost-effective fabrication. In this work, we

look at the problem from a different angle. Instead of addressing

the higher-level question of what to print, we examine lower-level

yet fundamental issues related to how to print a given object.

At the most elementary level, additive or layered fabrication oper-

ates by moving a print head which extrudes or fuses print material

layer by layer. When printing each layer, the print head follows a

prescribed tool path to fill the 2D region defined by the shape of

the printed object. Topologically, continuity of a tool path is crit-

ical to fabrication. A tool path discontinuity or contour plurality

forces an on-off switching of the print nozzle, negatively impacting

build quality and precision [Dwivedi and Kovacevic 2004; Ding

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for per-

sonal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not

made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear

this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components

of this work owned by others than the author(s) must be honored. Abstract-

ing with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on

servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a

fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org.

c

2016 Copyright

held by the owner/author(s). Publication rights licensed to ACM.

SIGGRAPH ’16 Technical Paper, July 24 - 28, 2016, Anaheim, CA

ISBN: 978-1-4503-4279-7/16/07

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2897824.2925958

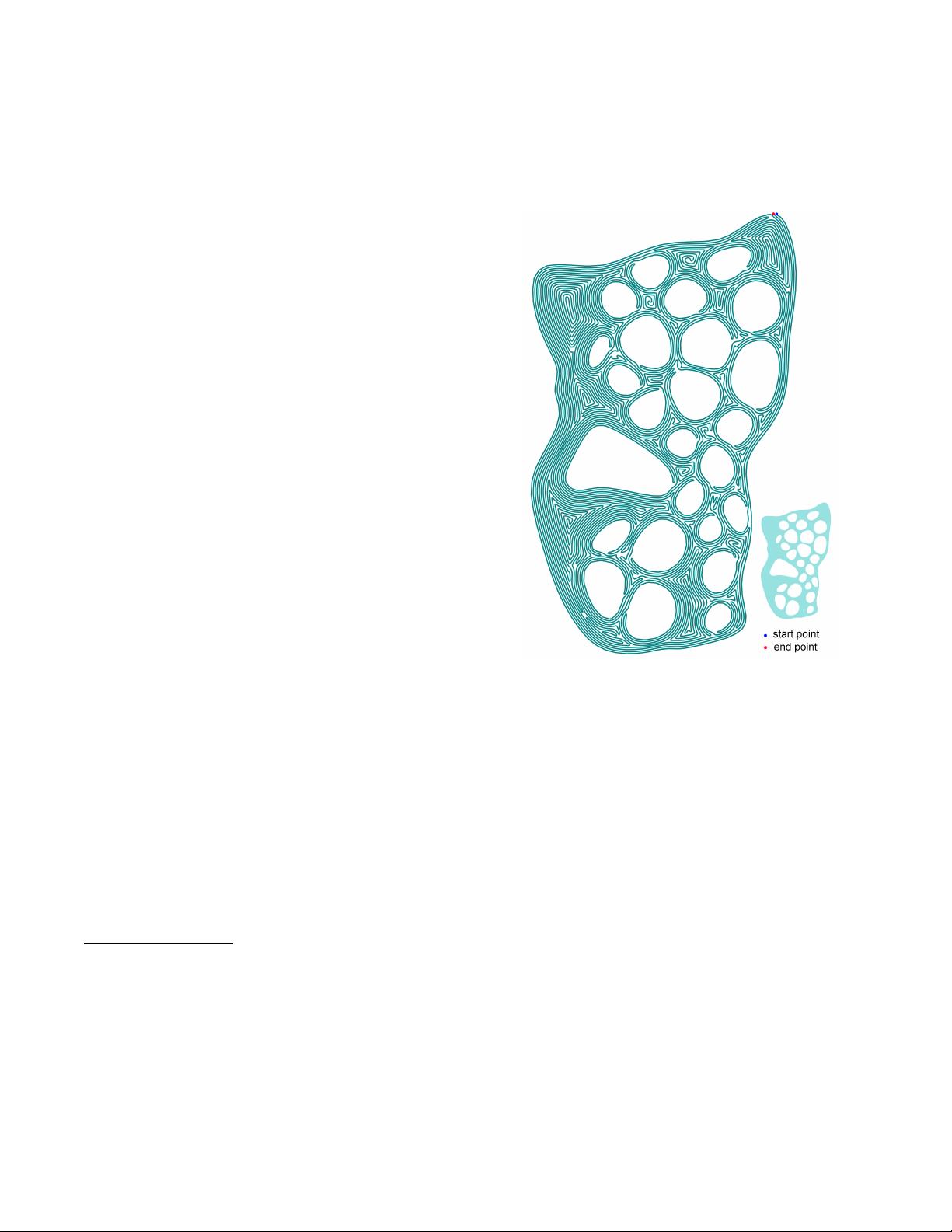

Figure 1: A new kind of “space-filling” curves called connected

Fermat spirals. Unlike classical space-filling curves which wind

and bend, the new curve is composed mostly of long, low-curvature

paths, making it desirable as a tool path fill patten for layered fabri-

cation. The tool path shown is continuous with start and end points

marked; the input 2D layer shape is displayed on the side.

et al. 2014]. Geometrically, sharp turns and corners are undesirable

since they lead to discretization artifacts at layer boundaries and

cause de-acceleration of the print head, both reducing print speed

and degrading fill quality [Jin et al. 2014].

Zigzag has been the most widely adopted fill pattern by today’s

3D printers due to its simplicity [Gibson et al. 2015]; see Figure 2

for various fill patterns. However, a zigzag fill consists of many

sharp turns, a problem that is amplified when printing shapes with

complex boundaries or hollow structures. A contour-parallel tool

path, formed by iso-contours of the Euclidean distance transform,

provides a remedy, but it leads to high contour plurality since the

iso-contours are disconnected from each other. A spiral fill pat-

tern, for simple shapes such as a square, is continuous. However,

for more complex shapes, both contour-parallel fills and spiral fills

tend to leave isolated “pockets” corresponding to singularities of

the distance transform, as shown in Figure 3(a). These pockets are

disconnected and result in path plurality. An intriguing geometry

question is whether a connected 2D region can always be filled by

a continuous pattern formed by one or more spirals.