Based on his experience during design and construction of several suspension bridges, and through his investigations

into accidents such as the collapse of the Wheeling Bridge in 1854, Roebling had acquired a profound understanding of the

aerodynamic problem. This is clearly indicated in his own description of the Brooklyn Bridge concept:

But my system of construction differs radically from that formerly practised, and I have planned the East River

Bridge [as the Brooklyn Bridge was initially called] with a special view to fully meet the destructive forces of a

severe gale. It is the same reason that, in my calculation of the requisite supporting strength so large a proportion has

been assigned to the stays in place of cables.

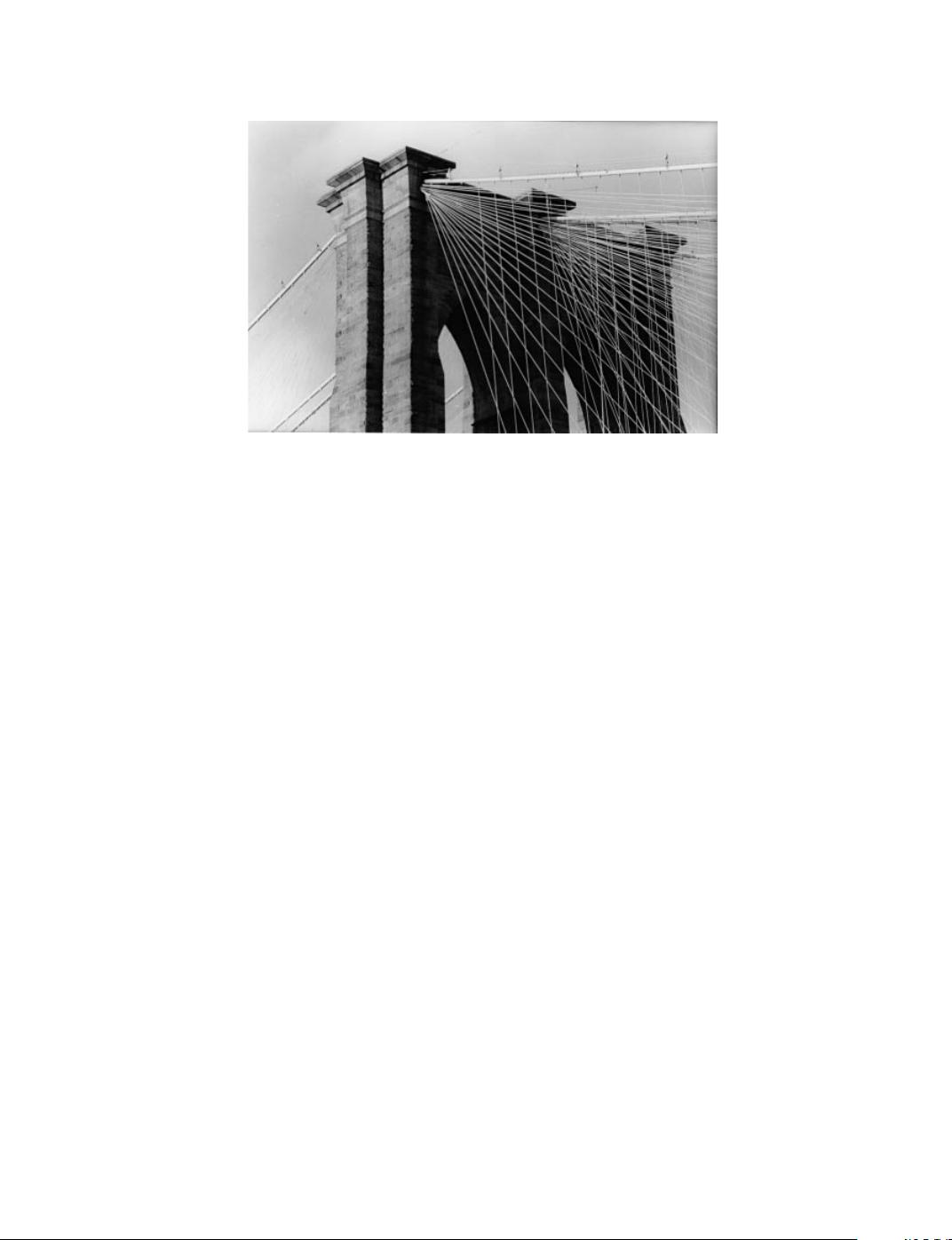

This description proves that Roebling knew very well that a cable stayed system is stiffer than the suspension system, and

the fact that the stays of the Brooklyn Bridge carry a considerable part of the load can be detected by the configuration of the

main cable having a smaller curvature in the regions where the stays carry a part of the permanent load than in the central

region, where all load is carried exclusively by the main cable.

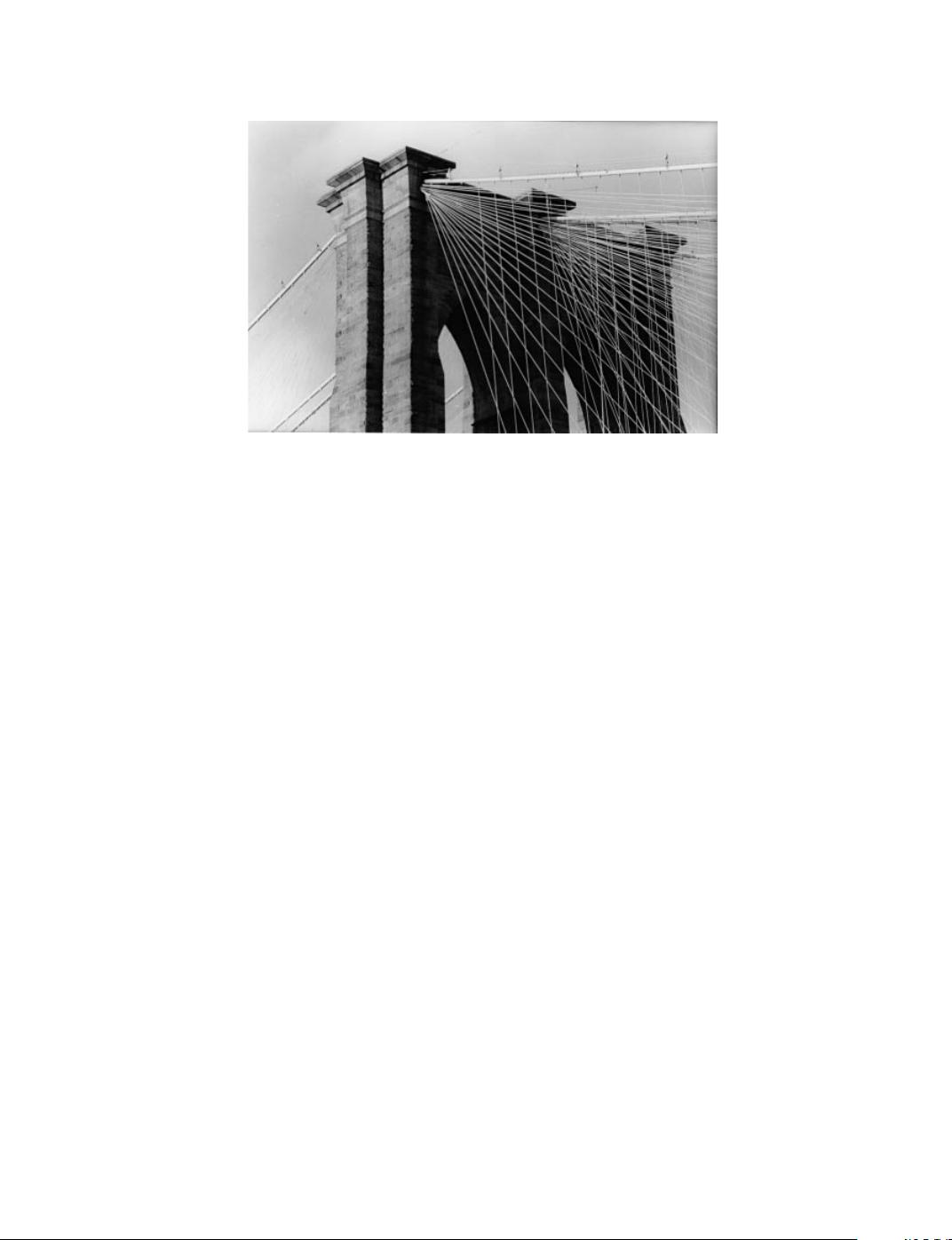

The efficiency of the stay cables (Figure 1.7) is clearly demonstrated by the following remark by Roebling: ‘The

supporting power of the stays alone will be 15 000 tons; ample to hold up the floor. If the cables were removed, the bridge

would sink in the center but would not fall.’

Roebling had started his engineering career at a time when the design of bridges was still more of an art, requiring

intuition and vision, than a science. Therefore, he had to acquire a profound understanding of the structural behaviour of

cable supported bridges through observations and by experience. He gradually learned how to design structures of great

complexity, as he could combine his intuitive understanding with relatively simple calculations, giving adequate

dimensions for all structural elements.

In the case of the Brooklyn Bridge, the system adopted is one of high indeterminateness as every stay is potentially a

redundant. A strict calculation based on the elastic theory with compatibility established between all elements would involve

numerical work of an absolutely prohibitive magnitude, but by stipulating reasonable distributions of forces between

elements and always ensuring that overall equilibrium was achieved, the required safety against failure could be attained.

After Roebling, the next generation of engineers was educated to concentrate their efforts on the calculations, which

required a stricter mathematical modelling. As systems of high statical indeterminateness would involve an insuperable

amount of numerical work if treated mathematically stringently, the layout of the structures had to be chosen with due

respect to the calculation capacity, and this was in many respects a step backwards. Consequently, a cable system such as

that used in the Brooklyn Bridge had to be replaced by much simpler systems.

The theories available for the calculation of suspension bridges in the second half of the nineteenth century were all

linear elastic theories, such as the theory by Rankine from 1858, dealing with suspension bridges where the deck comprised

Figure 1.7 The cable system of the Brooklyn Bridge at the pylon (USA)

Evolution of Cable Supported Bridges 11