1.3. The Regular-Expression Frame of Mind

As we'll soon see, complete regular expressions are built up from small building-block units.

Each individual building block is quite simple, but since they can be combined in an infinite

number of ways, knowing how to combine them to achieve a particular goal takes some

experience. So, this chapter provides a quick overview of some regular-expression concepts.

It doesn't go into much depth, but provides a basis for the rest of this book to build on, and

sets the stage for important side issues that are best discussed before we delve too deeply

into the regular expressions themselves.

While some examples may seem silly (because some are silly), they represent the kind of tasks

that you will want to do you just might not realize it yet. If each point doesn't seem to make

sense, don't worry too much. Just let the gist of the lessons sink in. That's the goal of this

chapter.

1.3.1. If You Have Some Regular-Expression Experience

If you're already familiar with regular expressions, much of this overview will not be new, but

please be sure to at least glance over it anyway. Although you may be aware of the basic

meaning of certain metacharacters, perhaps some of the ways of thinking about and looking

at regular expressions will be new.

Just as there is a difference between playing a musical piece well and making music, there is

a difference between knowing about regular expressions and really understanding them. Some

of the lessons present the same information that you are already familiar with, but in ways

that may be new and which are the first steps to really understanding.

1.3.2. Searching Text Files: Egrep

Finding text is one of the simplest uses of regular expressionsmany text editors and word

processors allow you to search a document using a regular-expression pattern. Even simpler is

the utility egrep. Give egrep a regular expression and some files to search, and it attempts to

match the regular expression to each line of each file, displaying only those lines in which a

match is found. egrep is freely available for many systems, including DOS, MacOS, Windows,

Unix, and so on. See this book's web site, http://regex.info, for links on how to obtain a copy

of egrep for your system.

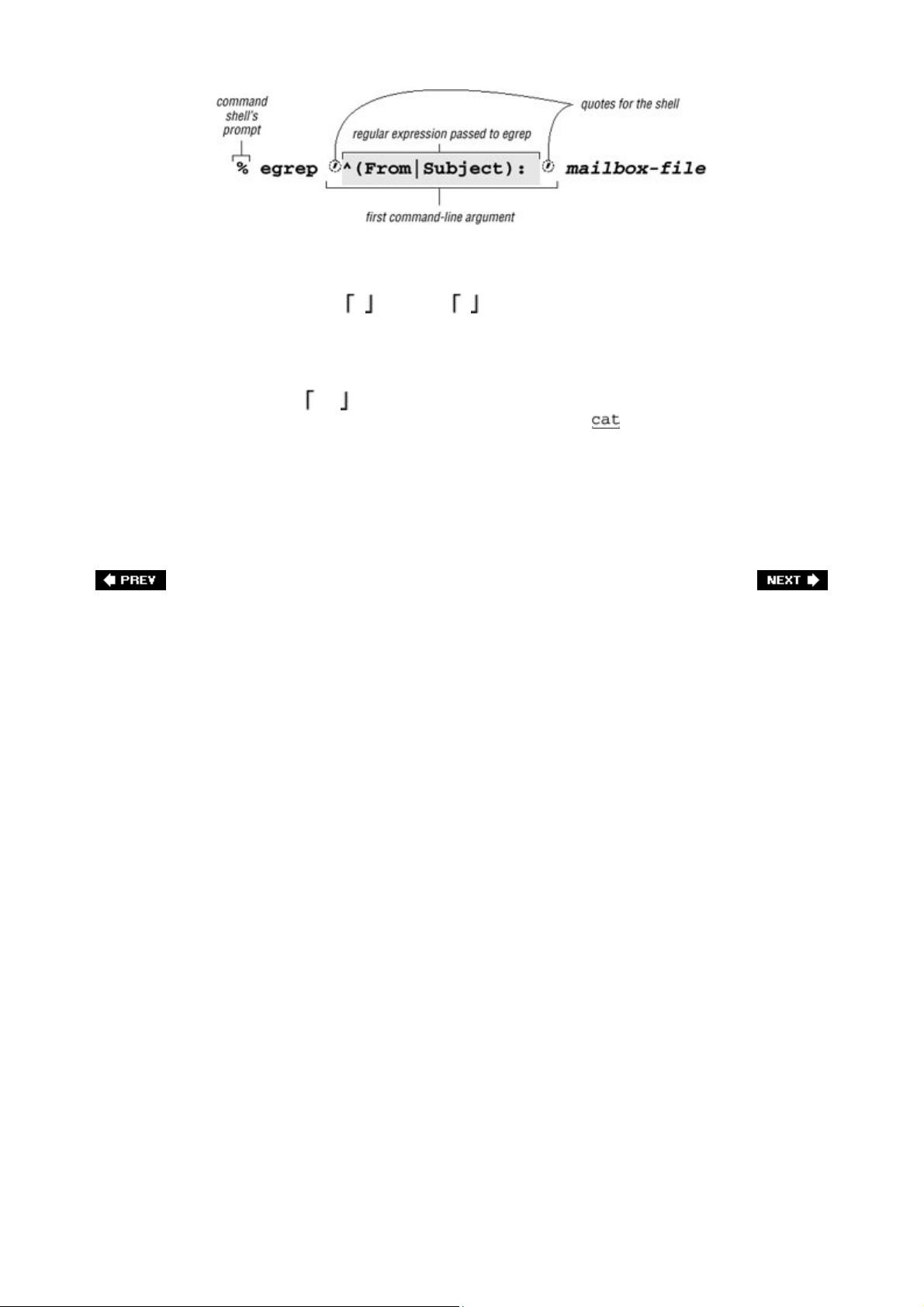

Returning to the email example from page 3, the command I actually used to generate a

makeshift table of contents from the email file is shown in Figure 1-1. egrep interprets the

first command-line argument as a regular expression, and any remaining arguments as the

file(s) to search. Note, however, that the single quotes shown in Figure 1-1 are not part of

the regular expression, but are needed by my command shell.

[ ]

When using egrep, I usually

wrap the regular expression with single quotes. Exactly which characters are special, in what

contexts, to whom (to the regular-expression, or to the tool), and in what order they are

interpreted are all issues that grow in importance when you move to regular-expression use in

fullfledged programming languagessomething we'll see starting in the next chapter.

[ ]

The command shell is the part of the system that accepts your typed commands and actually executes the programs you

request. With the shell I use, the single quotes serve to group the command argument, telling the shell not to pay too much attention

to w hat's inside. If I didn't use them, the shell might think, for example, a '

*

' that I intended to be part of the regular expression w as

really part of a filename pattern that it should interpret. I don't w ant that to happen, so I use the quotes to "hide" the metacharacters

from the shell. Window s users of COMMAND.COM or CMD.EXE should probably use double quotes instead.

Figure 1-1. Invoking egrep from the command line