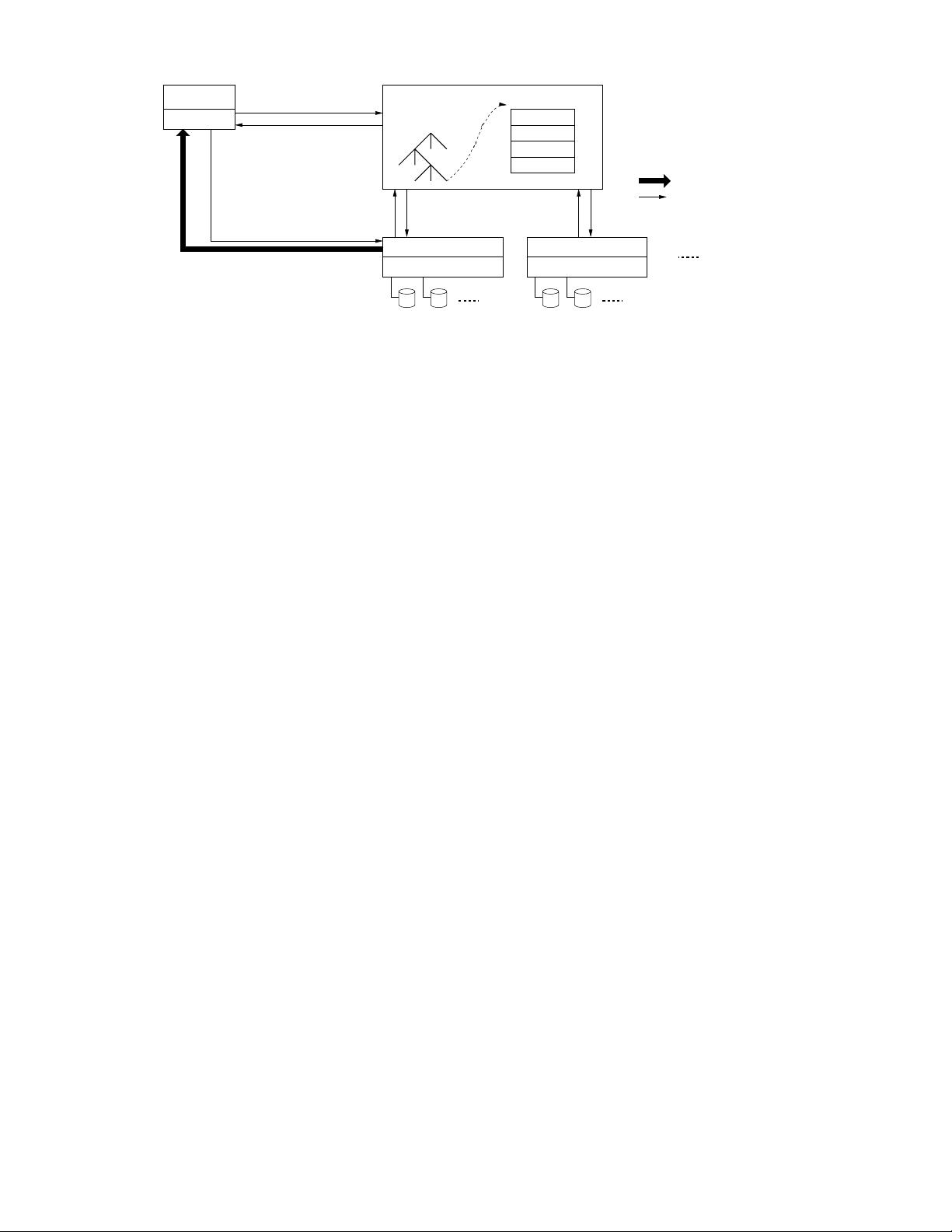

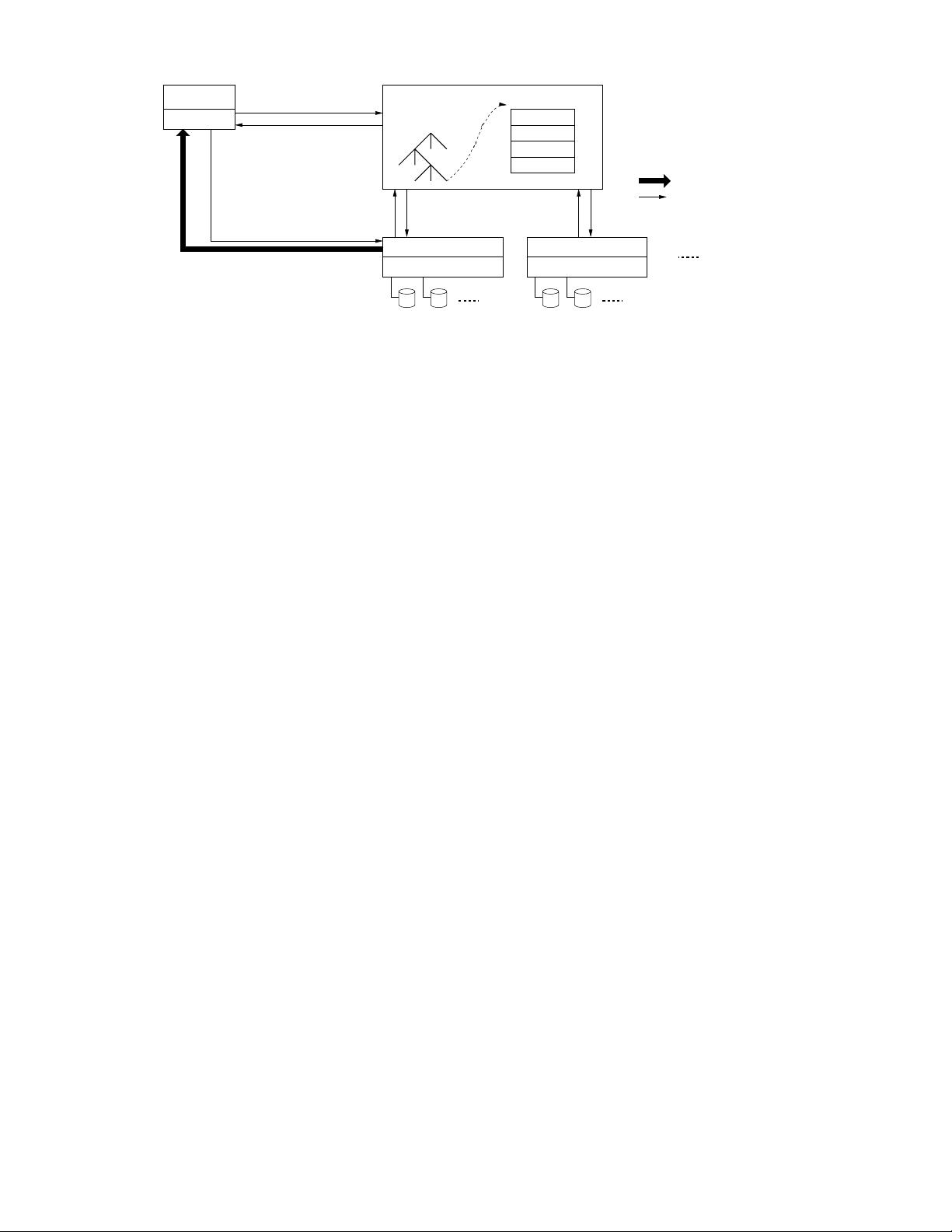

Legend:

Data messages

Control messages

Application

(file name, chunk index)

(chunk handle,

chunk locations)

GFS master

File namespace

/foo/bar

Instructions to chunkserver

Chunkserver state

GFS chunkserverGFS chunkserver

(chunk handle, byte range)

chunk data

chunk 2ef0

Linux file system Linux file system

GFS client

Figure 1: GFS Architecture

and replication decisions using global knowledge. However,

we must minimize its involvement in reads and writes so

that it does not become a bottleneck. Clients never read

and write file data through the master. Instead, a client asks

the master which chunkservers it should contact. It caches

this information for a limited time and interacts with the

chunkservers directly for many subsequent operations.

Let us explain the interactions for a simple read with refer-

ence to Figure 1. First, using the fixed chunk size, the client

translates the file name and byte offset specified by the ap-

plication into a chunk index within the file. Then, it sends

the master a request containing the file name and chunk

index. The master replies with the corresponding chunk

handle and locations of the replicas. The client caches this

information using the file name and chunk index as the key.

The client then sends a request to one of the replicas,

most likely the closest one. The request specifies the chunk

handle and a byte range within that chunk. Further reads

of the same chunk require no more client-master interaction

until the cached information expires or the file is reopened.

In fact, the client typically asks for multiple chunks in the

same request and the master can also include the informa-

tion for chunks immediately following those requested. This

extra information sidesteps several future client-master in-

teractions at practically no extra cost.

2.5 Chunk Size

Chunk size is one of the key design parameters. We have

chosen 64 MB, which is much larger than typical file sys-

tem block sizes. Each chunk replica is stored as a plain

Linux file on a chunkserver and is extended only as needed.

Lazy space allocation avoids wasting space due to internal

fragmentation, perhaps the greatest objection against such

a large chunk size.

A large chunk size offers several important advantages.

First, it reduces clients’ need to interact with the master

because reads and writes on the same chunk require only

one initial request to the master for chunk location informa-

tion. The reduction is especially significant for our work-

loads because applications mostly read and write large files

sequentially. Even for small random reads, the client can

comfortably cache all the chunk location information for a

multi-TB working set. Second, since on a large chunk, a

client is more likely to perform many operations on a given

chunk, it can reduce network overhead by keeping a persis-

tent TCP connection to the chunkserver over an extended

period of time. Third, it reduces the size of the metadata

stored on the master. This allows us to keep the metadata

in memory, which in turn brings other advantages that we

will discuss in Section 2.6.1.

On the other hand, a large chunk size, even with lazy space

allocation, has its disadvantages. A small file consists of a

small number of chunks, perhaps just one. The chunkservers

storing those chunks may become hot spots if many clients

are accessing the same file. In practice, hot spots have not

been a major issue because our applications mostly read

large multi-chunk files sequentially.

However, hot spots did develop when GFS was first used

by a batch-queue system: an executable was written to GFS

as a single-chunk file and then started on hundreds of ma-

chines at the same time. The few chunkservers storing this

executable were overloaded by hundreds of simultaneous re-

quests. We fixed this problem by storing such executables

with a higher replication factor and by making the batch-

queue system stagger application start times. A potential

long-term solution is to allow clients to read data from other

clients in such situations.

2.6 Metadata

The master stores three major types of metadata: the file

and chunk namespaces, the mapping from files to chunks,

and the locations of each chunk’s replicas. All metadata is

kept in the master’s memory. The first two types (names-

paces and file-to-chunk mapping) are also kept persistent by

logging mutations to an operation log stored on the mas-

ter’s local disk and replicated on remote machines. Using

a log allows us to update the master state simply, reliably,

and without risking inconsistencies in the event of a master

crash. The master does not store chunk location informa-

tion persistently. Instead, it asks each chunkserver about its

chunks at master startup and whenever a chunkserver joins

the cluster.

2.6.1 In-Memory Data Structures

Since metadata is stored in memory, master operations are

fast. Furthermore, it is easy and efficient for the master to

periodically scan through its entire state in the background.

This periodic scanning is used to implement chunk garbage

collection, re-replication in the presence of chunkserver fail-

ures, and chunk migration to balance load and disk space