11

REMARKS Bloomberg Businessweek October 11, 2021

Fintech companies that passed the

test presented by the pandemic have

seen their valuations soar

Money and data travel at warp speed, compressing space

and time, with less need for human intervention and more

demand for products to manage the ow. In the minds of

techies, this is a revolution in inclusion and democratization

for those left behind by thcentury banks. Fair enough: If

the best tech is like magic, banking hasn’t been magical for

some time. Startups are clearly better at ginning up eciency

through innovation.

But when instant gratication meets people’s pocket-

books, risks start to sneak in. Buy now, pay later programs

get more people to buy more things, but data in Australia

found in users paying late fees after missing repayments—

hardly a boon for equality. Robinhood Markets Inc., the

enabler for Reddit-fueled day traders, was ned million

by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority over mislead-

ing information and weak trading controls. The war for cus-

tomers means ntech rms lend to people more likely to

default, one study found.

Fintech rms’ use of data and models may also have bene

-

ted from the lack of a long economic downturn. “Risks associ-

ated with lending haven’t been tested,” says former hedge fund

manager Marc Rubinstein. Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

data show that from to there were U.S. bank

failures, but only since . And in a world where technol-

oy is winner-take-all, the algorithms that drive ntech suc-

cess could start to feel as exclusionary as the banks they seek

to replace. Their power is already being blamed for pushing up

home prices and discriminating against women and minorities.

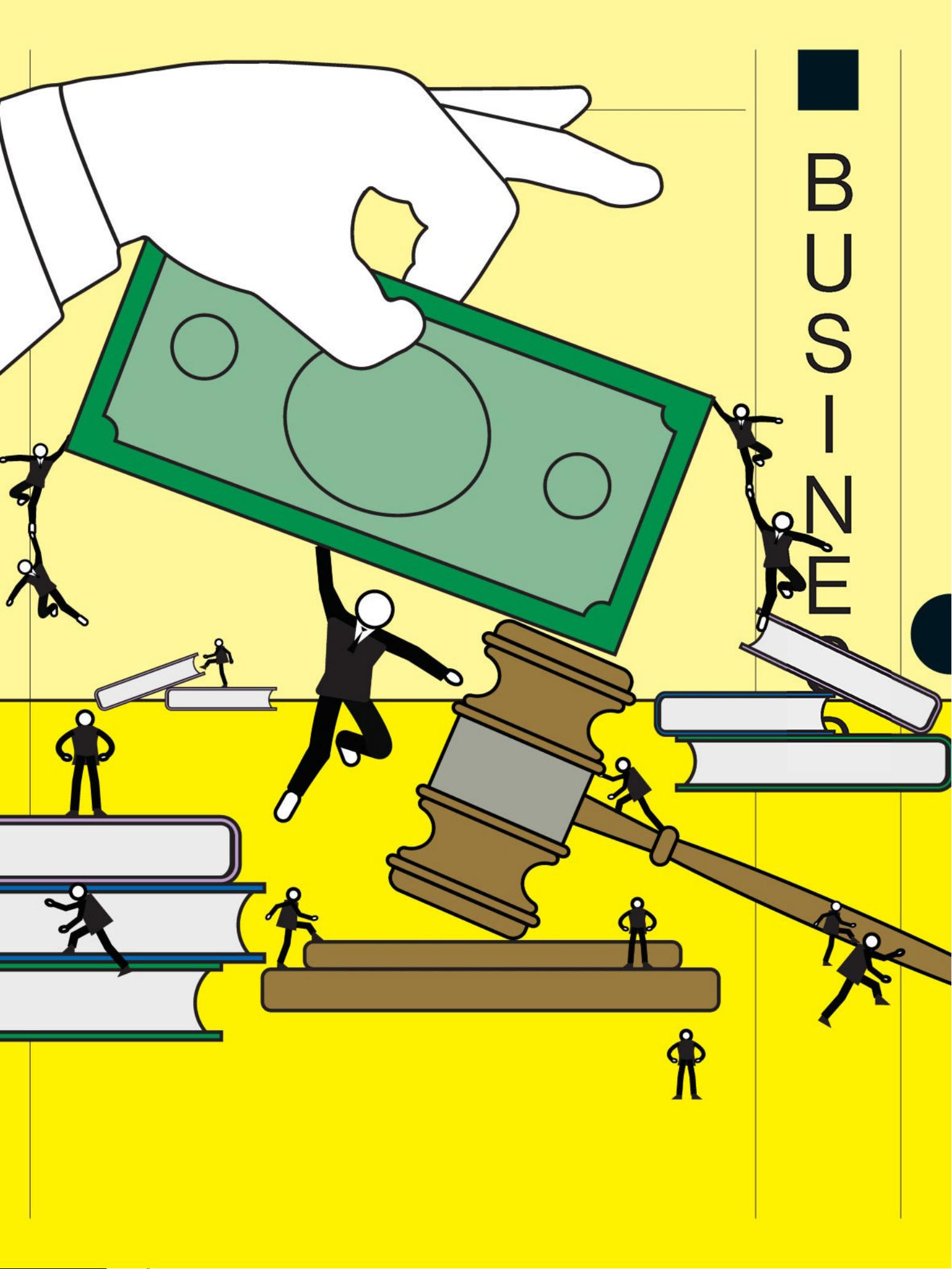

This all adds up to a regulatory headache as governments

struggle to hold the reins of a sector that’s growing fast and

oers plenty of reward but also plenty of risk. The Covid-

pandemic coincided with headline-grabbing ntech failures—

payments rm Wirecard AG and supply chain nance company

Greensill Capital—where red ags went unnoticed. The job of

having to beef up rules after each crisis isn’t made easier by

politicians calling on the tech sector to keep churning out uni-

corns to boost jobs. “When it comes to regulation, I worry,”

says economist Eswar Prasad, a Cornell professor and author

of The Future of Money. Regulators “seem to get overtaken by

rapid developments.”

Fintech’s disruptive potential was unleashed in mature

markets such as the U.S. only recently, thanks to a conuence

of factors: low interest rates, better technoloy, rising con-

sumer demand, and a more permissive attitude toward non-

bank nance. Eciency gains in software have kept products

coming. The relentless march of e-commerce has boosted

demand for new ways to pay. And venture capital is the fuel:

Global VC funding in ntech reached a record .billion

in the rst half of this year, according to KPMG. Since ,

ntech has raised trillion in equity.

All that money pressures startups to keep growing at

breakneck speed—and explains the shift from plain-vanilla

payments products to more heavily regulated nancial activ-

ities, according to Victor Basta, chief executive ocer of

investment bank DAI Magister. Regular bank accounts don’t

keep people swiping, unlike the stu keeping users awake at

night: crypto trading, investing, shopping, and loans.

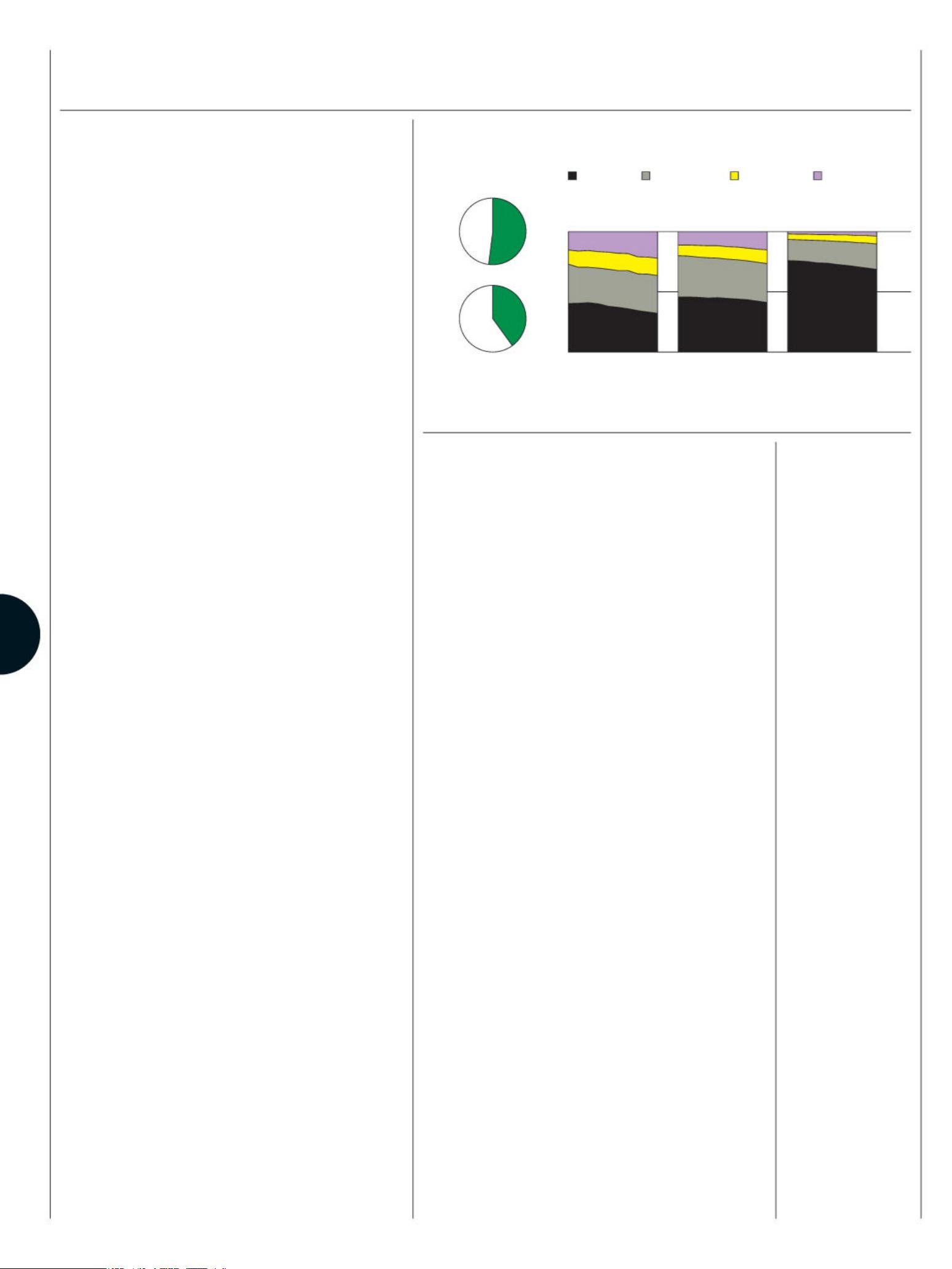

The pandemic was a key moment for the sector, as more

people were forced to turn to their smartphones for essen-

tials (government benets and savings) and not-so-essentials

(storming the barricades of GameStop Corp.). The ntechs

that passed the test have seen their valuations soar: Stripe

(billion), Klarna (.billion), Revolut (billion), and

Nubank (billion) rank among the most valuable pri-

vately owned unicorns in the world. On the stock market,

PayPal is worth billion, Square billion, and Adyen

billion (billion).

Traditional banks have been playing defense but also strik-

ing deals. Banks are one of ntech’s big funding sources:

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Citigroup Inc. participated in

and ntech deals, respectively, from to . Some

startups have chosen to become licensed banks themselves,

while big tech companies encroach into nancial territory

from the other direction: Amazon.com Inc. oers payments,

credit, and insurance with partner rms.

And the complexity of nancial regulation has opened

doors for tech startups. Some have exploited rules such as the

Durbin Amendment, which allows smaller banks to make more

money from card payments. Others have proted from laws

intended to improve competition, such as European Union

rules giving ntech companies access to bank account data.

The stunning collapse of Wirecard shows how easy it can

be to run rings around regulators. Here was a German bank

with access to deposits, a U.K.-regulated e-money institution,

and a payments rm on Visa Inc.’s and Mastercard Inc.’s net-

works, yet nobody acted on the red ags.

China—which had a head start on the U.S. and Europe in

ntech, thanks to years of cultivating revolutionary platform

companies such as Alibaba and Tencent—is likely the country

to watch. After a string of ntech scandals in the mid-s, the

government is cracking down on the platforms for perceived

monopolizing of sensitive data and hindering fair competition.

Governments have to do more to reduce the risks while

amplifying the benets of ntech innovation. Stronger

consumer protection and improvements to nancial liter-

acy would help. Regulators are also trying a more active

approach to technoloy, oering sandbox-type controlled

environments where ntech rms can experiment and grow.

But it’s hard to escape the feeling that a lot of the risks com-

ing down the pike are unpredictable and many-headed and

that regulators won’t keep up. With central bankers deter-

mined not to be disrupted in their management of the econ-

omy, perhaps another line from Hamlet will prove prescient:

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be.”