compensating for the failures, flaws, and limitations inherent in your hardware or software. Almost

every physical effect discussed in this book, from indirect light bouncing off walls to the translucency

in human skin, can be simulated through careful texturing, lighting, and compositing, even when your

software doesn’t fully or automatically simulate everything for you. When someone sees the picture or

animation that you have lit, they want to see a complete, believable picture, not hear excuses about

which program you used.

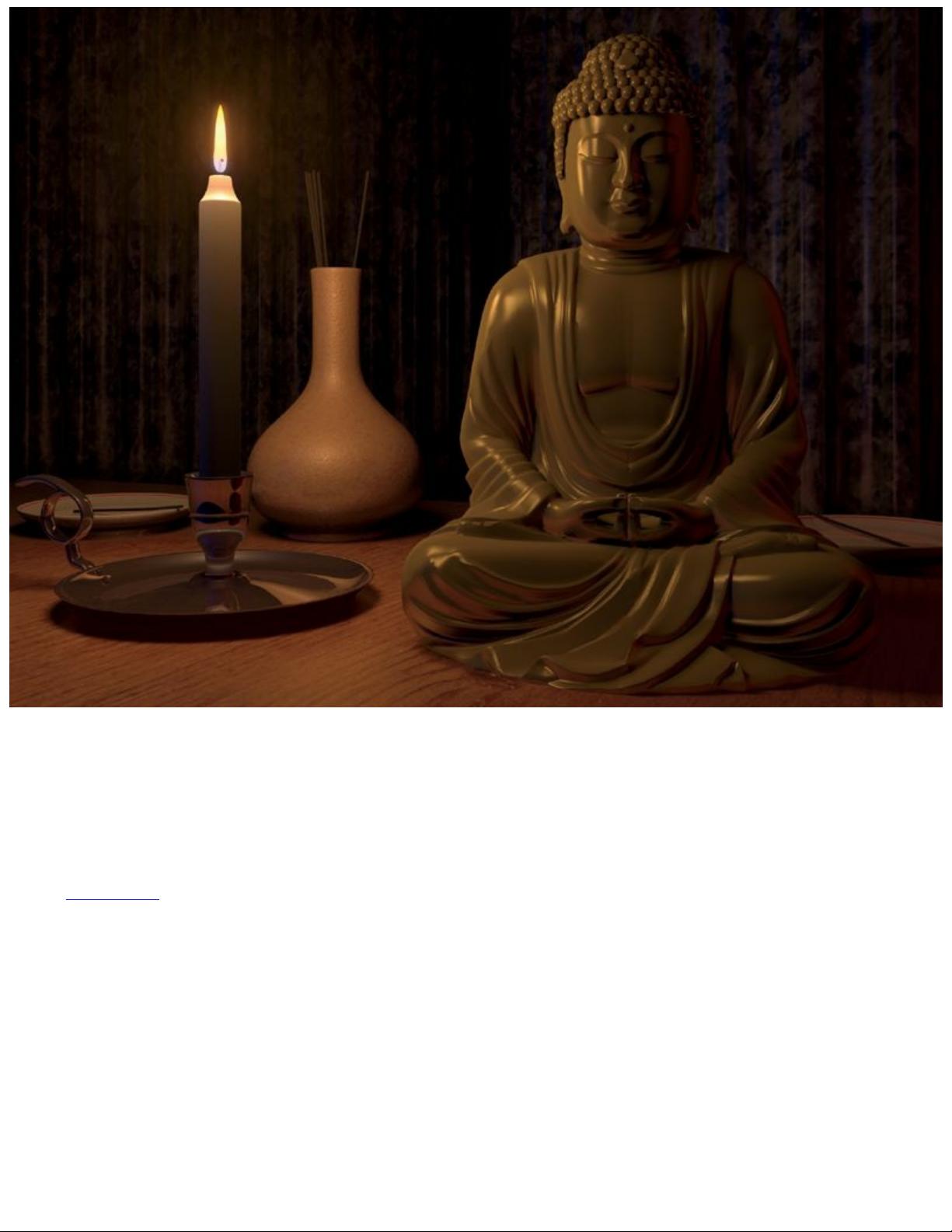

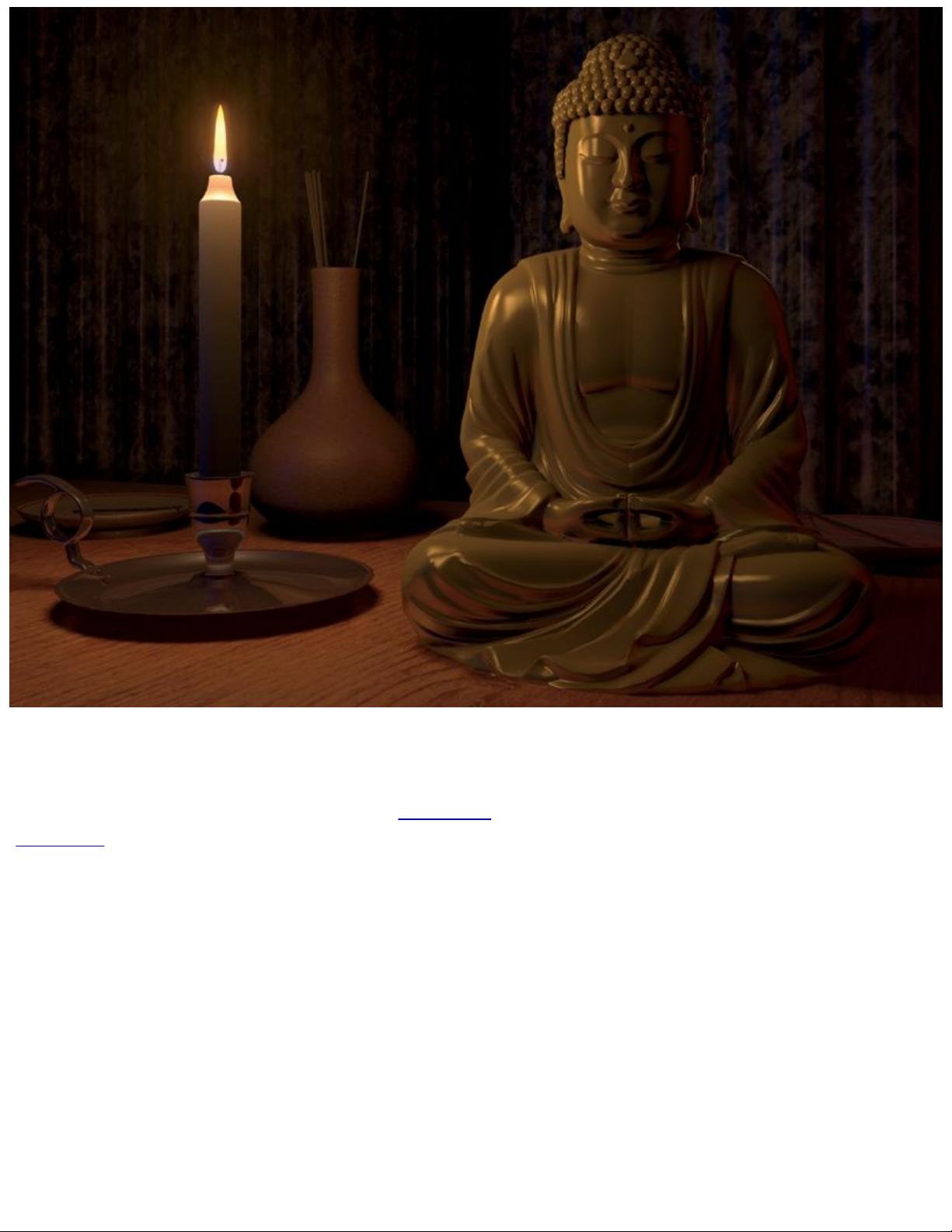

Enhancing Shaders and Effects

Frequently in 3D graphics you find it necessary to add lights to a scene to help communicate the

identity of different surfaces and materials. For example, you may create a light that adds highlights to

a character’s eyes to make them look wetter, or puts a glint of light onto an aluminum can to make it

look more metallic. Many effects that, in theory, you could create exclusively by developing and

adjusting surfaces and textures on 3D objects are often helped along during production by careful

lighting you design to bring out the surface’s best attributes. No matter how carefully developed and

tested the shaders on a surface were before you started to light, it’s ultimately your job to make sure

all that is supposed to be gold actually glitters.

Effects elements such as water, smoke, and clouds often require special dedicated lights. The effects

department will create the water droplets falling from the sky on a rainy night, but it’s your job as a

lighting artist to add specular lights or rim lights to make the drops visible. Effects such as explosions

are supposed to be light sources, so you need to add lights to create an orange glow on the

surrounding area when there’s an explosion.

Maintaining Continuity

When you work on longer projects such as feature films, many people are involved in lighting

different shots. Even though the lighting is the work of multiple artists, you need to make sure that

every shot cuts together to maintain a seamless experience for the audience. Chapter 12 discusses

strategies that groups of lighters use to maintain continuity, including sharing lighting rigs for sets and

characters, duplicating lighting from key shots to other shots in a sequence, and reviewing shots in

context within their sequence to make sure the lighting matches.

In visual effects, continuity becomes a more complex problem, because you need to integrate your 3D

graphics with live-action plates. During a day of shooting, the sun may move behind a cloud while

one shot is filmed, and it may be brighter outside when another shot is filmed. Although integrating a

creature or spaceship with the lighting from the background plate may be the key to making your shot

believable, the continuity of the sequence as a whole is just as high a priority, and sometimes you

need to adjust your shot’s lighting to match the lighting in adjacent shots as well.

Directing the Viewer’s Eye

In a well-lit scene, your lighting should draw the viewer’s eye to areas that are important to the story,

animation, or key parts of the shot. Chapter 7 will cover more about how composition and staging

work and what makes a part of the frame attract the viewer’s eye or command attention.

Besides making the intended center of interest visible, good lighting avoids distracting the audience

with anything else. When you are viewing an animated film, the moment something unintended catches

your eye—whether it’s a strange flicker or artifact, a highlight where it doesn’t belong, or a shadow

that cuts across a character—your eye has been pulled away from the action and, worse than that,