6 Setting the stage: why ab initio molecular dynamics?

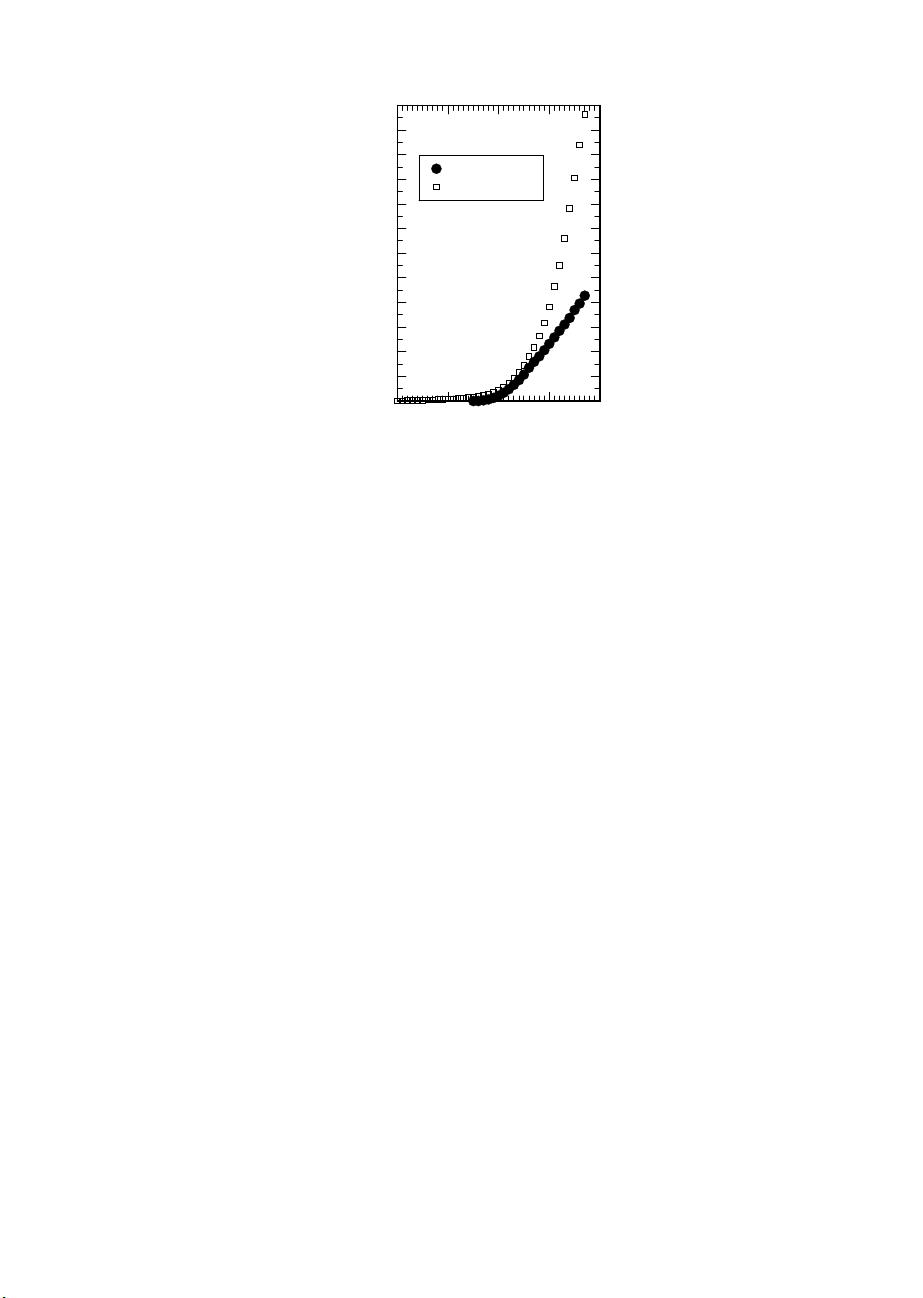

order of magnitude estimate, the advantage of ab initio molecular dynamics

vs. calculations relying on the computation of a global potential energy

surface amounts to about 10

3N−6−M−n

. The crucial point is that for a

given statistical accuracy (that is for M and n fixed and independent of N)

and for a given electronic structure method, the computational advantage

of “on-the-fly” approaches grows like ∼ 10

N

with system size. Thus, Car–

Parrinello methods always outperform the traditional three-step approaches

if the system is sufficiently large and complex. Conversely, computing global

potential energy surfaces beforehand and running many classical trajectories

afterwards without much additional cost always pays off for a given system

size N like ∼ 10

M+n

if the system is small enough so that a global potential

energy surface can be computed and parameterized.

Of course, considerable progress has been achieved in accelerating the

computation of global potentials by carefully selecting the discretization

points and reducing their number, choosing sophisticated representations

and internal coordinates, exploiting symmetry and decoupling of irrelevant

modes, implementing efficient sampling and smart extrapolation techniques

and so forth. Still, these improvements mostly affect the prefactor but not

the overall scaling behavior, ∼ 10

N

, with the number of active degrees of

freedom. Other strategies consist of, for instance, reducing the number of

active degrees of freedom by constraining certain internal coordinates, rep-

resenting less important ones by a (harmonic) bath or by friction forces, or

building up the global potential energy surface in terms of few-body frag-

ments. All these approaches, however, invoke approximations beyond those

of the electronic structure method itself. Finally, it is evident that the com-

putational advantage of the “on-the-fly” approaches diminishes as more and

more trajectories are needed for a given (small) system. For instance, exten-

sive averaging over many different initial conditions is required in order to

calculate scattering or reactive cross-sections quantitatively. Summarizing

this discussion, it can be concluded that ab initio molecular dynamics is the

method of choice to investigate large and “chemically complex” systems.

Quite a few reviews, conference articles, lecture notes, and overviews

dealing with ab initio molecular dynamics have appeared since the early

1990s [38, 228, 338, 460, 485, 486, 510, 563, 564, 669, 784, 933, 934, 936–

938, 943, 1099, 1103, 1104, 1123, 1209, 1272, 1306, 1307, 1498, 1512, 1544]

and the interested reader is referred to them for various complementary view-

points. This book originates from the Lecture Notes [943] “Ab initio molec-

ular dynamics: Theory and implementation” written by the present authors

on the occasion of the NIC Winter School 2000 titled “Modern Methods and

Algorithms of Quantum Chemistry”. However, it incorporates in addition