during one hour. In San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico, the total number of touches

was 180. In contrast, the total in Paris was 110, and in London it was 0. One problem

with interpreting these data is that the kinds of people who go to cafes in San Juan, Paris,

and London may be quite different. It is also entirely possible that those who spend much

of their time in cafes are not representative of the general population. These issues of

representativeness apply to many observational studies.

Evaluation

Jourard’s (1966) findings do not really tell us why there is (or was, in 1966) much more

touching in San Juan than in London. It is possible that Londoners are simply less friendly

and open, but there are several other possibilities (e.g. Londoners are more likely to go

to cafes with business colleagues). The general issue here is that it is often very hard to

interpret or make sense of the data obtained from observational studies, because we can

only speculate on the reasons why the participants are behaving in the ways that we

observe.

Another issue was raised by Coolican (1994) in his discussion of the work of Whyte

(1943). Whyte joined an Italian street gang in Chicago, and became a participant observer.

The problem he encountered in interpreting his observations was that his presence in the

gang influenced their behaviour. A member of the gang expressed this point as follows:

“You’ve slowed me down plenty since you’ve been down here. Now, when I do some-

thing, I have to think what Bill Whyte would want me to know about it and how I can

explain it.”

CONTENT ANALYSIS

Content analysis is used when originally qualitative information is reduced to numerical

terms. Content analysis started off as a method for analysing messages in the media,

including articles published in newspapers, speeches made by politicians on radio and

television, various forms of propaganda, and health records. More recently, the method

of content analysis has been applied more widely to almost any form of communication.

As Coolican (1994, p. 108) pointed out:

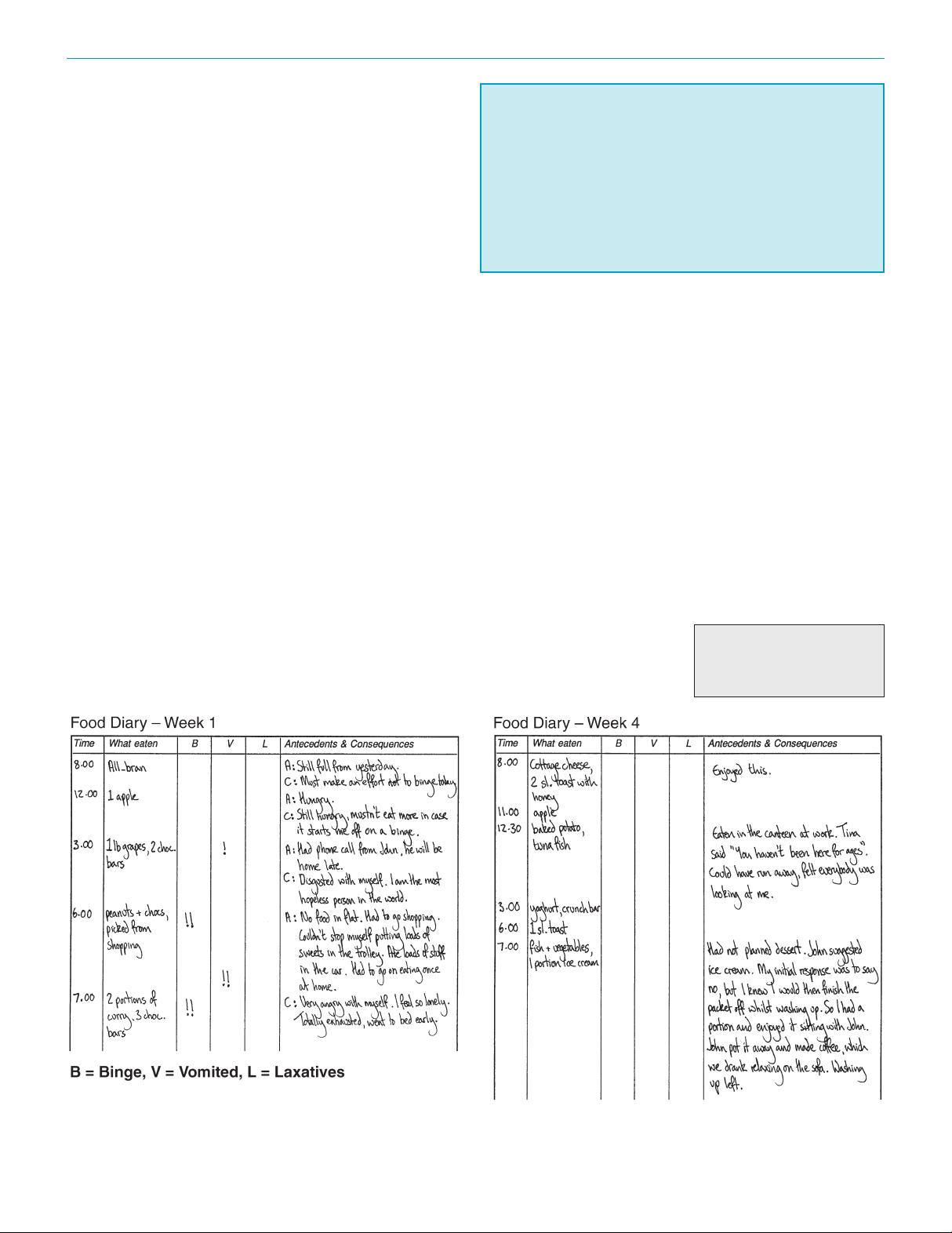

The communications concerned were originally those already published, but

some researchers conduct content analysis on materials which they ask people

to produce, such as essays, answers to interview questions, diaries, and verbal

protocols [detailed records].

One of the types of communication that has often been studied by content analysis is

television advertising. For example, McArthur and Resko (1975) carried out a content

analysis of American television commercials. They found that 70% of the men in these

commercials were shown as experts who knew a lot about the products being sold. In

contrast, 86% of the women in the commercials were shown only as product users. There

was another interesting gender difference: men who used the products were typically

promised improved social and career prospects, whereas women were promised that their

family would like them more.

More recent studies of American television commercials (e.g. Brett & Cantor, 1988)

indicate that the differences in the ways in which men and women are presented have been

reduced. However, it remains the case that the men are far more likely than women to be

presented as the product expert.

The first stage in content analysis is that of sampling, or deciding what to select from

what may be an enormous amount of material. For example, when Cumberbatch (1990)

carried out a study on over 500 advertisements shown on British television, there were

two television channels showing advertisements. Between them, these two channels were

broadcasting for about 15,000 hours a year, and showing over 250,000 advertisements.

Accordingly, Cumberbatch decided to select only a sample of advertisements taken from

prime-time television over a two-week period.

6 Research methods

KEY TERM

Content analysis: a method

involving the detailed study of,

for example, the output of the

media, speeches, and literature.

PIP_S3.qxd 16/12/04 4:47 PM Page 6