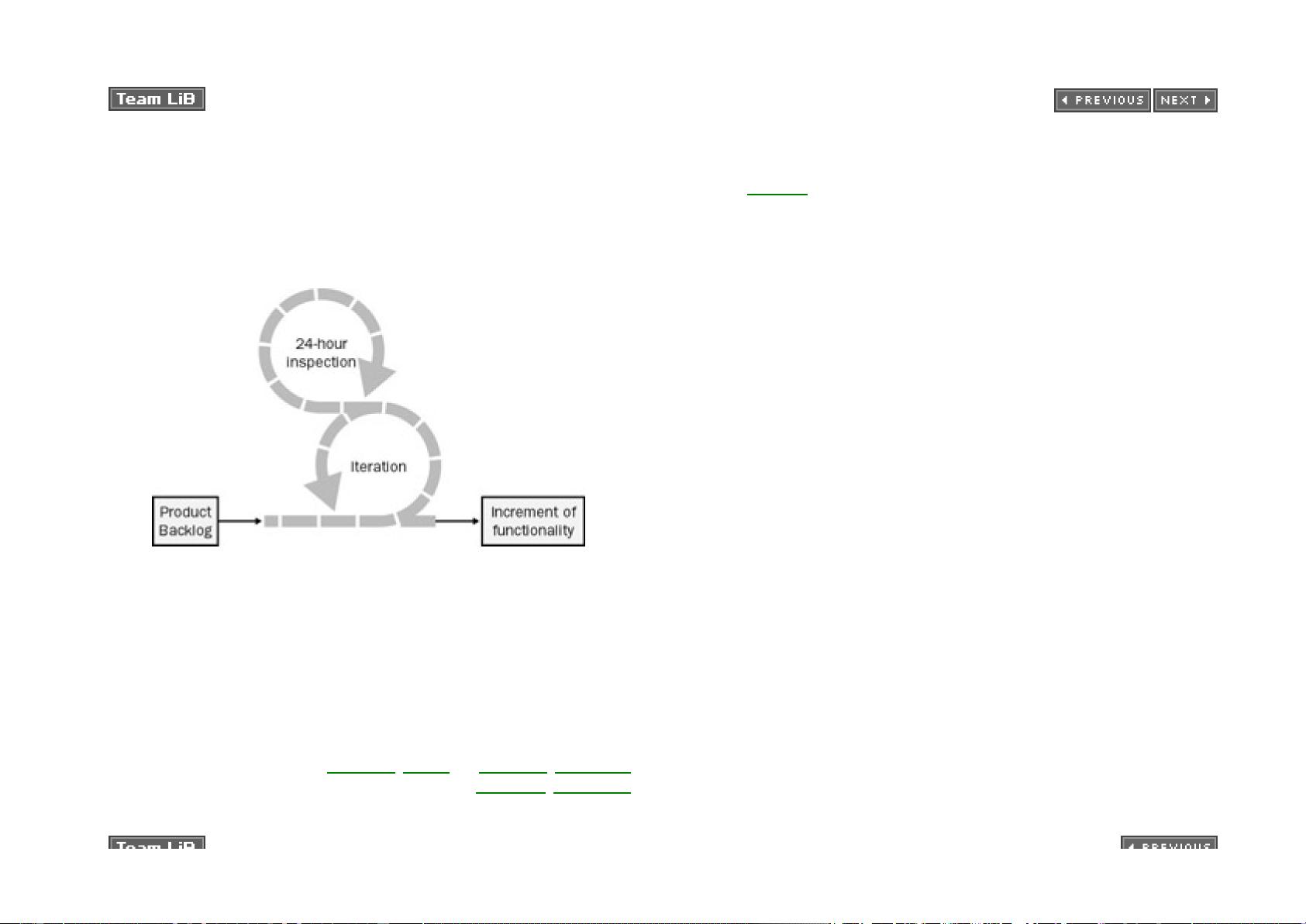

Scrum Flow

A Scrum project starts with a vision of the system to be developed. The vision might be vague at first, perhaps stated in market terms rather than system terms, but it will becom e

clearer as the project moves forward. The Product Owner is responsible to those funding the project for delivering the vision in a manner that maximizes their ROI. The Product Owne r

formulates a plan for doing so that includes a Product Backlog. The Product Backlog is a list of functional and nonfunctional requirements that, when turned into functionality, wil l

deliver this vision. The Product Backlog is prioritized so that the items most likely to generate value are top priority and is divided into proposed releases. The prioritized Produc t

Backlog is a starting point, and the contents, priorities, and grouping of the Product Backlog into releases usually changes the moment the project starts—as should be expected .

Changes in the Product Backlog reflect changing business requirements and how quickly or slowly the Team can transform Product Backlog into functionality .

All work is done in Sprints. Each Sprint is an iteration of 30 consecutive calendar days. Each Sprint is initiated with a Sprint planning meeting, where the Product Owner and Team ge t

together to collaborate about what will be done for the next Sprint. Selecting from the highest priority Product Backlog, the Product Owner tells the Team what is desired, and th e

Team tells the Product Owner how much of what is desired it believes it can turn into functionality over the next Sprint. Sprint planning meetings cannot last longer than eigh t

hours—that is, they are time-boxed to avoid too much hand-wringing about what is possible. The goal is to get to work, not to think about working .

The Sprint planning meeting has two parts. The first four hours are spent with the Product Owner presenting the highest priority Product Backlog to the Team. The Team questions

him or her about the content, purpose, meaning, and intentions of the Product Backlog. When the Team knows enough, but before the first four hours elapses, the Team selects as

much Product Backlog as it believes it can turn into a completed increment of potentially shippable product functionality by the end of the Sprint. The Team commits to the Product

Owner that it will do its best. During the second four hours of the Sprint planning meeting, the Team plans out the Sprint. Because the Team is responsible for managing its own work,

it needs a tentative plan to start the Sprint. The tasks that compose this plan are placed in a Sprint Backlog; the tasks in the Sprint Backlog emerge as the Sprint evolves. At the start

of the second four- hour period of the Sprint planning meeting, the Sprint has started, and the clock is ticking toward the 30-day Sprint time-box.

Every day, the team gets together for a 15-minute meeting called a Daily Scrum. At the Daily Scrum, each Team member answers three questions: What have you done on this

project since the last Daily Scrum meeting? What do you plan on doing on this project between now and the next Daily Scrum meeting? What impediments stand in the way of you

meeting your commitments to this Sprint and this project? The purpose of the meeting is to synchronize the work of all Team members daily and to schedule any meetings that the

Team needs to forward its progress.

At the end of the Sprint, a Sprint review meeting is held. This is a four-hour, time-boxed meeting at which the Team presents what was developed during the Sprint to the Product

Owner and any other stakeholders who want to attend. This informal meeting at which the functionality is presented is intended to bring people together and help them collaboratively

determined what the Team should do next. After the Sprint review and prior to the next Sprint planning meeting, the ScrumMaster holds a Sprint retrospective meeting with the Team.

At this three-hour, time-boxed meeting, the ScrumMaster encourages the Team to revise, within the Scrum process framework and practices, its development process to make it more

effective and enjoyable for the next Sprint. Together, the Sprint planning meeting, the Daily Scrum, the Sprint review, and the Sprint retrospective constitute the empirical inspection

and adaptation practices of Scrum. Take a look at Figure 1-3 to see a diagram of the Scrum process.

This document was created by an unregistered ChmMagic, please go to http://www.bisenter.com to register it. Thanks .