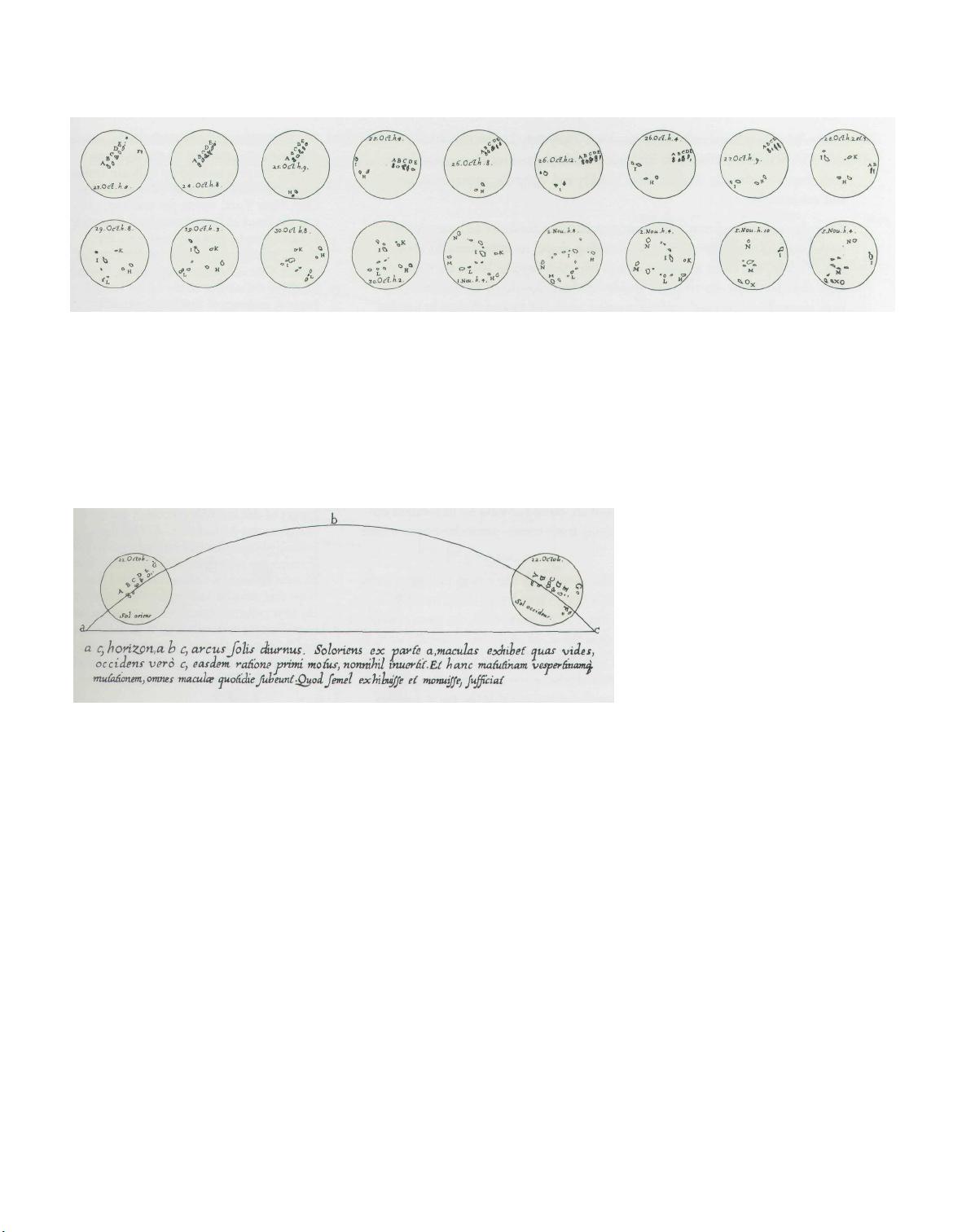

always being produced and others dissolved. They vary in duration from one or

two days to thirty or forty. For the most part they are of most irregular shape, and

their shapes continually change, some quickly and violently, others more slowly

and moderately.

They also vary in darkness, appearing sometimes to condense and sometimes to

spread out and rarefy. In addition to changing shape, some of them divide into

three or four, and often several unite into one; this happens less at the edge of the

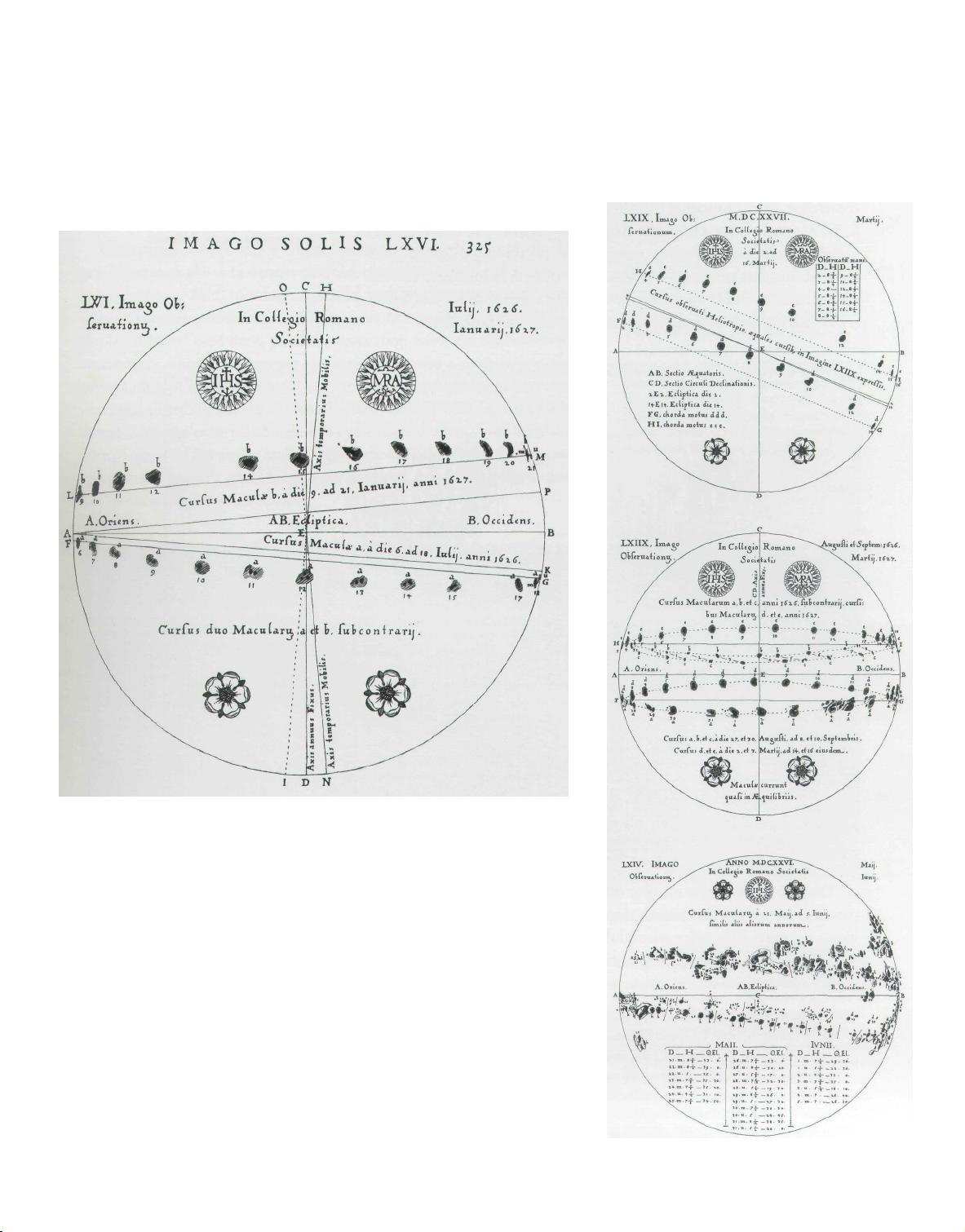

sun's disk than in its central parts. Besides all these disordered movements they

have in common a general uniform motion across the face of the sun in parallel

lines. From special characteristics of this motion one may learn that the sun is

absolutely spherical, that it rotates from west to east around its own center, carries

the spots along with it in parallel circles, and completes an entire revolution in

about one lunar month. Also worth noting is the fact that the spots always fall

in one zone of the solar body, lying between the two circles which bound the

declinations of the planets - that is, they fall within 28° or 29° of the sun's equator.

The different densities and degrees of darkness of the spots, their changes of shape,

and their collecting and separating are evident directly to our sight, without any

need of reasoning, as a glance at the diagrams which I am enclosing will show. But

that the spots are contiguous to the sun and are carried around by its rotation can

only be deduced and concluded by reasoning from certain particular events which

our observations yield.

First, to see twenty or thirty spots at a time move with one common movement is

a strong reason for believing that each does not go wandering about by itself, in the

manner of the planets going around the sun. . . . To begin with, the spots at their

first appearance and final disappearance near the edges of the sun generally seem to

have very little breadth, but to have the same length that they show in the central

parts of the sun's disk. Those who understand what is meant by foreshortening on

a spherical surface will see this to be a manifest argument that the sun is a globe,

that the spots are close to its surface, and that as they are carried on that surface

toward the center they will always grow in breadth while preserving the same

length. . . . this maximum thinning, it is clear, takes place at the point of greatest

foreshortening....

I have since been much impressed by the courtesy of nature, which thousands of

years ago arranged a means by which we might come to notice these spots, and

through them to discover things of greater consequence. For without any instru-

ments, from any little hole through which sunlight passes, there emerges an image

of the sun with its spots, and at a distance this becomes stamped upon any surface

opposite the hole. It is true that these spots are not nearly as sharp as those seen

through the telescope, but the majority of them may nevertheless be seen. If in

church some day Your Excellency sees the light of the sun falling upon the pave-

ment at a distance from some broken window pane, you may catch this light upon

a flat white sheet of paper, and there you will perceive the spots. I might add that

nature has been so kind that for our instruction she has sometimes marked the sun

with a spot so large and dark as to be seen merely by the naked eye, though the

false and inveterate idea that the heavenly bodies are devoid of all mutation or al-

teration has made people believe that such a spot was the planet Mercury coming

between us and the sun, to the disgrace of past astronomers.

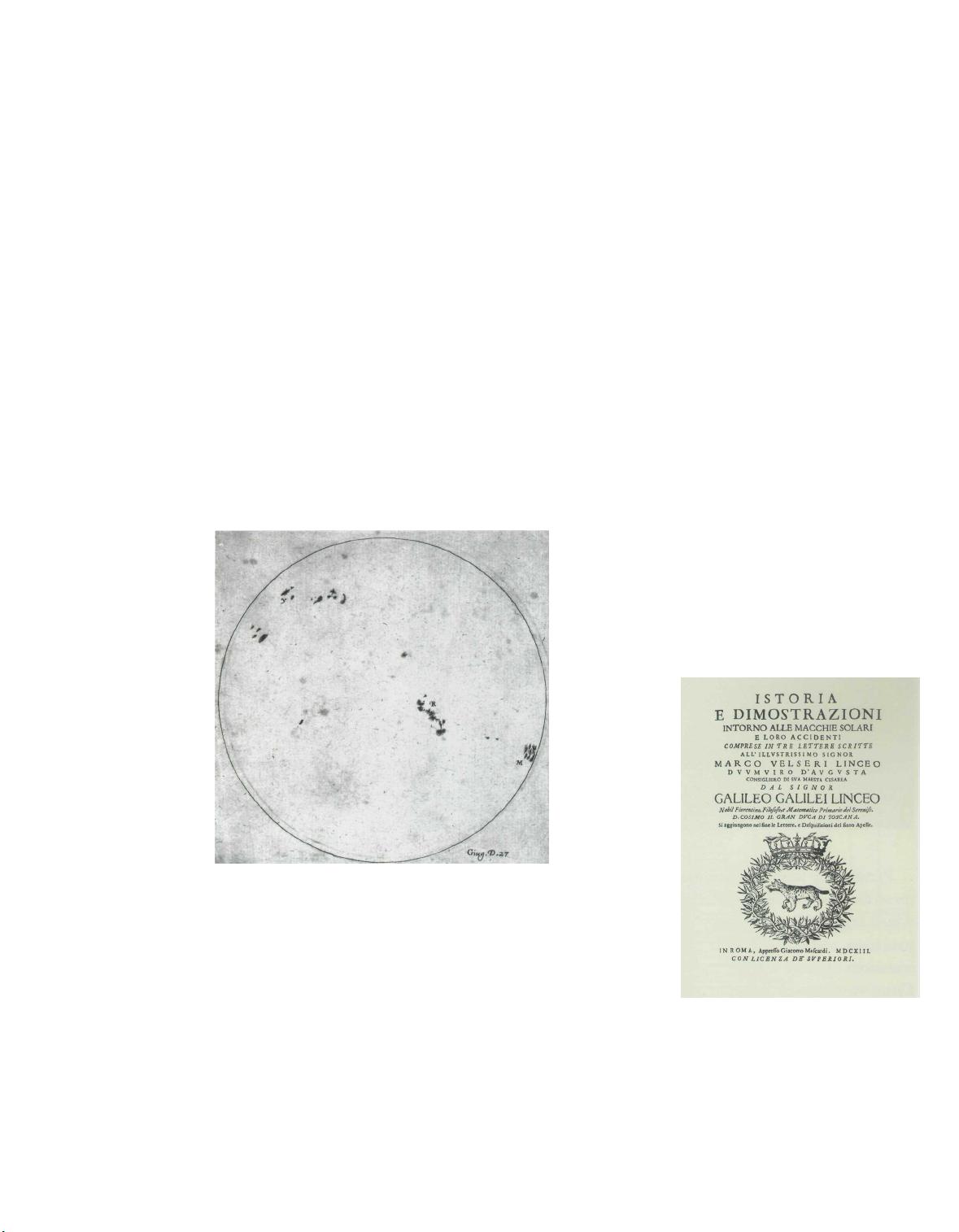

12

12

Galileo Galilei, History and Demonstrations

Concerning Sunspots and Their Phenomena

(Rome, 1613), translated by Stillman Drake,

Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo (Garden

City, New York, 1957), pp. 106-107, 116-

117. Galileo had been through all this once

before when he first saw craters on the

moon, another supposedly perfect celestial

sphere. One of Galileo's opponents, "who

admitted the surface of the moon looked

rugged, maintained that it was actually

quite smooth and spherical as Aristotle had

said, reconciling the two ideas by saying

that the moon was covered with a smooth

transparent material through which moun-

tains and craters inside it could be discerned.

Galileo, sarcastically applauding the ingenu-

ity of this contribution, offered to accept it

gladly — provided that his opponent would

do him the equal courtesy of allowing him

then to assert that the moon was even more

rugged than he had thought before, its sur-

face being covered with mountains and

craters of this invisible substance ten times

as high as any he had seen. At Pisa the

leading philosopher had refused even to look

through the telescope; when he died a few

months afterward, Galileo expressed the

hope that since he had neglected to look at

the new celestial objects while on earth, he

would now see them on his way to hea-

ven." Stillman Drake, "Introduction: Sec-

ond Part," Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo

(Garden City, New York, 1957), p. 73.

20 ENVISIONING INFORMATION