Robust additive spread-spectrum embedding 11

subset that maps to b, so that the relationship of b

= g(I

1

) is deterministically en-

forced. To minimize perceptual distortion, I

1

should be as close to I

0

as possible.

A simple example is odd-e ven embedding, whereby a closest even number is used

as I

1

to embed a “0” and a closest odd number is used to embed a “1.” The em-

bedded bit is extracted simply by checking the odd-even parity, w hich does not

require the knowledge of original I

0

. There can be other constraints imposed on

I

1

for robustness considerations. For example, the enforcement can be done in a

quantized domain with a step size Q [18, 37]. The odd-even enforcement can also

be extended to higher dimensions involving features computed from a set of host

components.

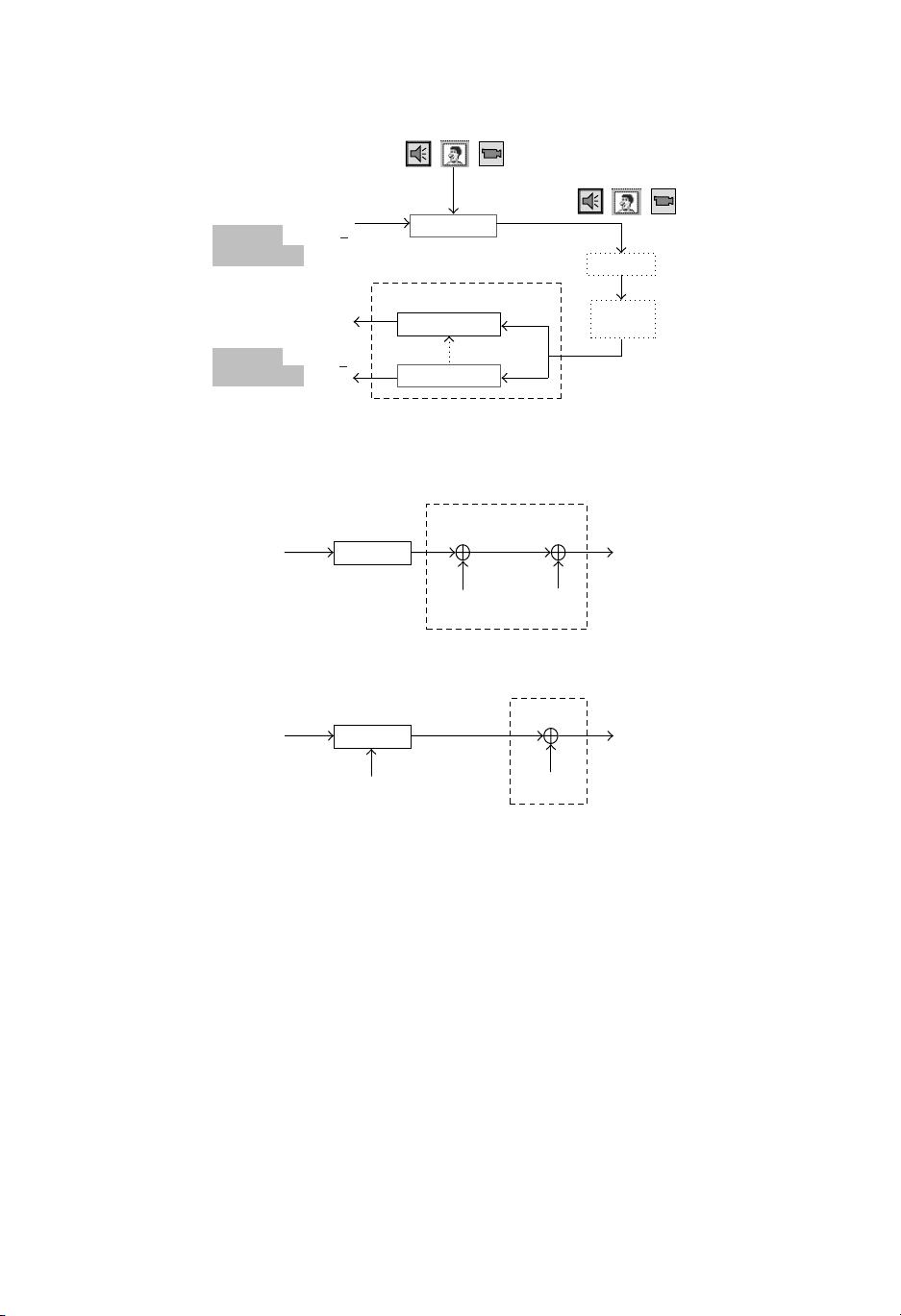

Under blind detection where the host signal is not available at the detector

and becomes a major source of noise for Type-I embedding, the number of bits

that can be reliably embedded by Type-II is much higher than that of Type-I

when the noise is not strong [18, 38, 39]. On the other hand, Type-I is com-

monly used for robust embedding with strong noise (especially when noise be-

comes much stronger than the watermark) as well as for nonblind detection. Mo-

tivated by Costa’s information-theoretical result [40], distortion compensation

has been proposed to be incorporated into quantization-based enforcement em-

bedding [39, 41, 42], where the enforcement is combined linearly with the host

signal to form a watermarked signal. The optimal scaling factor is a func tion of

WNR and will increase the number of bits that can be embedded. This distortion-

compensated embedding can be viewed a s a combination of Type-I and Type-II

embedding.

2.2. Robust additive spread-spectrum embedding

With a big picture in mind, we now zoom in to the problem of robust embedding,

which serves as an important building block for embedding fingerprints into the

multimedia content.

Fingerprinting multimedia requires the use of robust data embedding meth-

ods that are capable of withstanding attacks that adversaries might employ to re-

move the fingerprint. Although there are many techniques that have been pro-

posed for embedding information in multimedia signals [17], in the sequel we

will use the spread-spectrum additive embedding technique for illustrating the

embedding of fingerprint signals into multimedia. Spread-spectr um embedding

has proven robust against a number of signal processing operations (such as lossy

compression and filtering) and attacks [23, 24]. With appropriately chosen fea-

tures and additional alignment procedures, the spread-spectrum watermark can

survive moderate geomet ric distortions, such as rotation, scale, shift, and cropping

[43, 44]. Further, information-theoretic studies suggest that it is nearly capacity

optimal when the original host s ignal is available in detection [38, 39]. The combi-

nation of robustness and c apacity makes spread-spectrum embedding a promising

technique for protecting multimedia. In addition, as we will see in later chapters,

its capability of putting multiple marks in overlapped regions also limits the effec-

tive strategies mountable by colluders in fingerprinting applications.

A print edition of this book can be purchased at

http://www.hindawi.com/spc.4.html

http://www.amazon.com/dp/9775945186